Date: 23 January 2026

Tobias Rist of Fraunhofer IWM and speaker at glasstec 2024 explains in this interview how an innovative laser process shapes glass in a targeted, localised manner, makes for new structures and improves load-bearing behaviour – and the benefits this brings for architecture and industry.

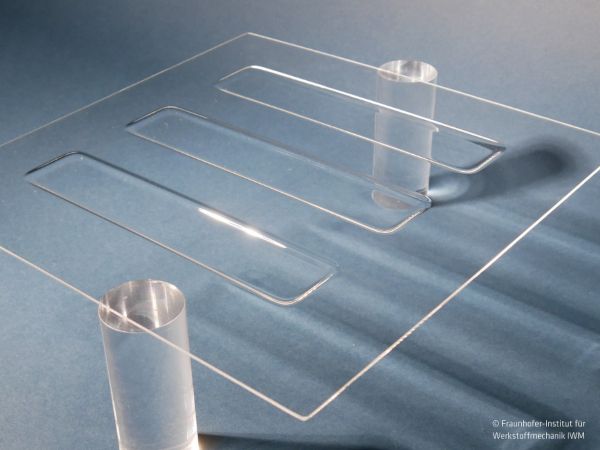

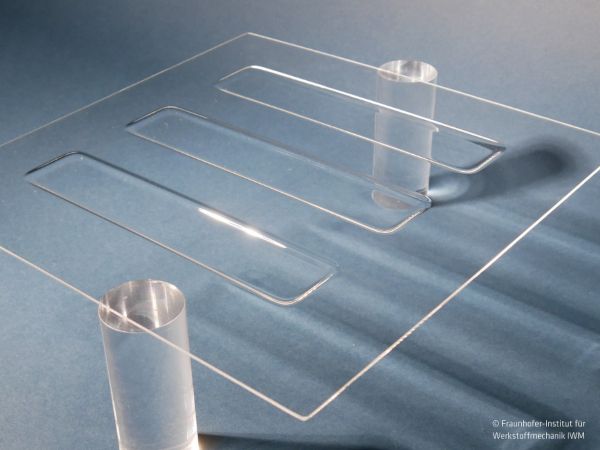

Today, flat glass can be bent or “gravity sunk” selectively without losing its flat structural properties. This is made possible by a new laser process that produces geometrically precise, localised structures and achieves bending radii of up to 1.5 times the glass thickness. This technology opens up new potential for design, statics and sustainable construction.

Mr Rist, you are developing a laser-based process at the Fraunhofer IWM Institute that permits flat glass to be shaped selectively. Can you briefly explain how this process works in practice and what the laser exactly does to the glass?

Tobias Rist: Our process comes into its own in particular where the component geometry still has even surfaces. The glass is heated up in a furnace and the laser selectively introduces additional heat into the parts to be shaped. Through the laser this can be very precise and targeted/localised so that very small bending radii in the order of magnitude of 1.5 times the thickness of the glass can be realised. The remaining glass around it stays so cool that the outstanding properties of the original flat glass are retained and at the same time warm enough to avoid breakage due to thermal stresses.

When you say structural stiffening what does this mean for glass in concrete terms? What types of bends, folds or localised curved geometries can you produce by laser and how does the load-bearing behaviour of a glass sheet change compared to flat glass?

Tobias Rist: In laser shaping we distinguish between two different shaping processes: firstly, the classic bending of flat glass where the flat glass is bent across the entire length of the sized part. This process is characterised by the fact that the glass thickness in the bent area remains almost the same as for the rest. The glass is just “re-directed”. Secondly, we speak of “gravity-sunk” glass. In this process a sub-area of the sized glass sheet sinks into shape under its own weight by means of gravity. During the process the glass in the transition area from outside to inside surface becomes thinner. The transition area therefore has a thinner wall thickness. Since we work with a laser we can produce free forms. The gravity sinking process is a form-free process because the outer glass keeps everything in place – only the outside needs reinforcement. The inner surface can be designed freely. The gravity-sunk depth is limited by the transition area, its width and the glass thickness. Gravity sinking to 2 or 3 times the glass thickness is easily feasible.

Where do you see the most important applications for laser-shaped, structurally stiffened glass in architecture and industry over the coming years? And which advantages do you expect over conventionally bent glass when it comes to design freedom, energy efficiency and economy?

Tobias Rist: On the one hand, I could well imagine all-glass corner glazing in residential buildings, for example. Imagine you are standing in your kirchen and observe the beauty of nature also across the corner while washing the salad. Next to unique transparency these glazed corners have the advantage of avoiding thermal bridges in the corners thereby solving the problems of condensation water and mould formation. The targeted/localised gravity sunk areas lend themselves to introducing structures into the glass, which can be used as design features, on the one hand, and serve to stiffen the pane against later undesired bending, on the other. The structures produced increase the load-bearing capacity since the bending stiffness is proportional to the area moment of inertia, which is increased across the depth of the structure. This effect entails structural stiffening and can be compared to corrugated sheet metal or ridges on light commercial vehicle roofs. Thinner glass with the same performance saves resources and energy in production and contributes to sustainable building.

600450

600450

Add new comment