First presented at GPD 2017

Abstract

In the European Union, Member States are allowed to set minimum performance requirements to construction products available on their market. It is preferred not to have EU wide performance requirements, so that individual Member States regulate such performance individually taking into account their own building stock and climate specificities.

In Member States that have correctly and timely implemented the European Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) (2010) there are requirements related to the energy performance (holistic approach) of new buildings and buildings receiving major renovation. This should in theory be complemented by prescriptive energy performance requirements for building components with a very strong influence on the energy performance of the whole structure, such as windows.

In 2017, the European Union reviews the EPBD which represents an opportunity to assess the state-of-play in the Member States and, eventually, propose measures to improve the assessment of the energy performance of windows in national schemes. A study for Glass for Europe provides a clear picture of the minimum requirements for window replacement in the residential sector across the different Member States and reflects on if/how the European framework could be improved to further support the Member States with additional guidance.

Introduction

The potential of energy savings in the European Union’s (EU) building sector through efficient building products is well known1 and acknowledged by the European Commission in its Energy Union framework strategy (European Union, 2015). In a recent study commissioned by the European Commission2, windows in the EU are considered responsible for 24% of the EU heating demand and 9% of the cooling demand. These high figures can be explained by the percentage of sub-optimal windows installed in EU residential sector. A recent study estimates that over 85% of glazed areas in EU buildings are equipped either with single glazing or uncoated double glazing (TNO, 2011). When considering that over 1billion of new windows will be sold by 2030 in the European Union, according to market forecasts available in the same European Commission study, the energy saving potential for the European building is substantial.

Despite the priority given to energy efficient buildings in Europe and the vast amount of energy that can be saved if consumers opt for energy-efficient windows, putting in place meaningful regulatory measures at EU level to foster building renovation and push the market has shown to be a challenging task.

The Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) is the main EU policy driver affecting the energy use in buildings. Member States that have correctly and timely implemented the EPBD introduced energy performance (holistic approach) requirements for new buildings and buildings receiving major renovation. These do not exclude the existence of prescriptive requirements for building components with a very strong influence on the energy performance of the whole structure (or components with relatively long lifetimes), including windows. In other words, under the EU legislative structure, it is preferred not to have EU wide performance requirements, so that individual Member States can set minimum performance requirements to construction products available on their market, taking into account their own building stock and climate specificities.

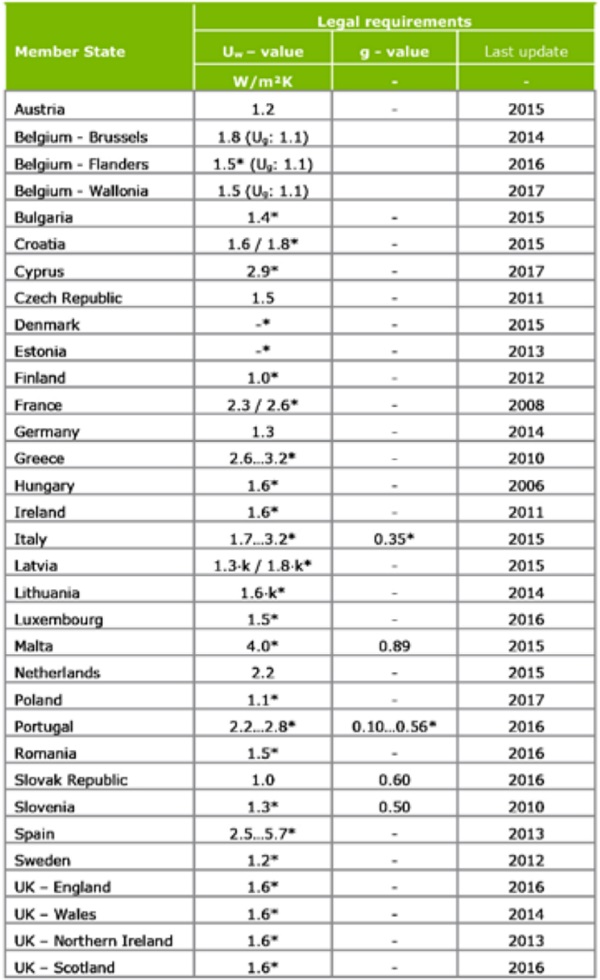

A recent study commissioned by Glass for Europe to Ecofys (figure I), in the context of the current revision of the EPBD, shows that all Member States but one (i.e. Estonia) have introduced such requirements for windows. The Glass for Europe’s study by Ecofys is based on existing studies, legal national documents, and interviews with contact person from all Member States, including the three Belgium regions and four UK regions. The findings of the study highlight divergences between Member States in terms of methodology, ambition and effective implementation. The present paper will present these key differences and reflect on if/how the European framework could be improved to further support the Member States with additional guidance.

Main learnings

Calculation of the windows’ energy performance

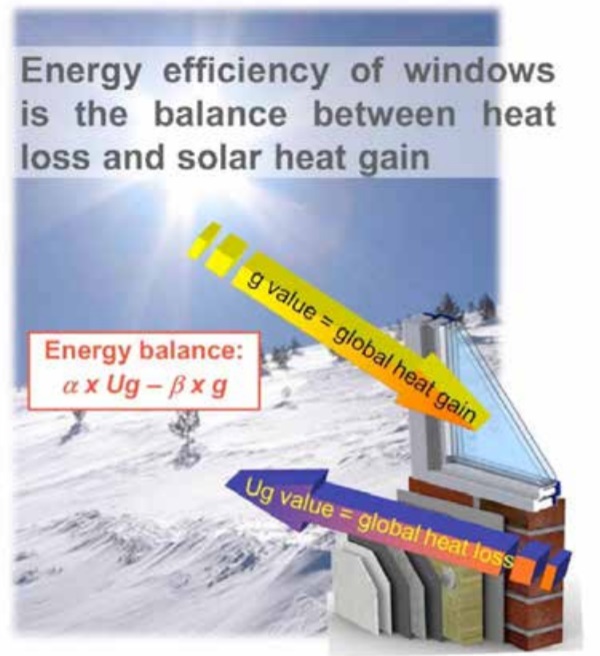

In 27 EU Member States (out of 28) minimum requirements for windows have been introduced. These requirements can be regrouped in three categories: minimum requirements based on the U-value (being Uwvalue or Ug-value), on the Uw-value and g-value separately or on the energy balance combining both the Uw-value and g-value.

A vast majority of Member States have introduced in their national legislations minimum requirements for windows based solely on the heat transition coefficient for the whole window (glass and frame); i.e. Uw-value (see table 1). In total, 18 EU Member States make use of this value only; i.e. Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Spain and Sweden. For the three Belgian regions, Latvia and Lithuania the minimum requirements are based solely or partially on the Ug-value (heat transition coefficient for the transparent area).

Only five countries include legal requirements for the total energy transmittance factor of glazing system, i.e. g-value, to complement the requirement based on a Uw-value: Italy, Malta, Portugal, Slovak Republic and Slovenia. Despite significant yearly solar irradiance levels, countries from the South of Europe and Central Europe (Western or Eastern Europe) such as Spain, Greece, France, Germany, Czech Republic or Bulgaria are not considering the solar heat gains in their energy performance calculations and minimum requirements.

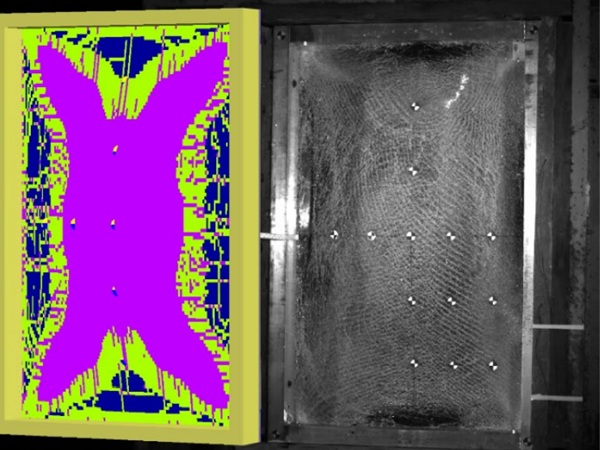

Only Denmark applies minimum requirements for windows based on the energy balance approach combining both the solar heat gains and heat losses of the window into a single value (figure 2). However, the United-Kingdom allows legal requirements to be met either by way of meeting minimum requirements based on the Uw-value (i.e. 1.6 W/m²K) or band of the Window Energy Rating label (i.e. Band C or better) which is calculated based on the energy balance approach.

Despite the fact that the energy balance has been widely recognized by window professionals has the only effective way to assess the energy performance of a window, e.g. eco-design preparatory study Lot 32 on windows4, this methodology is only applied in Denmark and the United-Kingdom. A vast majority of Member States focuses the requirements on the sole Uw-value, not taking into account the energy gains from passive solar irradiance; while five Member States introduced additional separated requirements based on the g-value which does not provide a balance between the heat gains and heat losses over one year.

Minimum requirements based on the Uw-value

As underlined previously, Estonia is the only EU Member States which does not have set minimum legal requirements for replacement of windows in the residential buildings. All other EU Member States have introduced minimum requirements based on the Ug-value, being by way of a Uw-value, Ug-value (i.e. three regions in Belgium) or integrated in the energy balance calculation (i.e. Denmark and UnitedKingdom WER label).

From a formalistic point of view, all Member States are compliant with the EU legislation prescriptions. However, when looking at the minimum requirements set in the national legislations, two fundamental problems arise in an important number of Member States: the sub-optimal minimum requirements set in the national regulation and the absence of updates.

As mentioned in the introduction of this paper, under the European legislation (EPBD), it is the Member States’ responsibility to set the minimum requirements for building components with a strong influence on the energy performance of the whole structure. The flexibility given to Member States is meant to give room for national regulations to take into account their own building stock and climate specificities. However, when looking at the requirements set for windows in some countries, one can hardly argue that the very low minimum requirements are resulting from national climate or building stock. For instance, two of the EU founding countries, namely France and the Netherlands, have set minimum requirements respectively at 2.3 W/m²K and 2.2 W/m²K. In comparison, Germany minimum requirements for windows is set at 1.3 W/m²K. At the moment, the two countries with the most demanding minimum requirements are the Slovak Republic and Finland with a Uw-value of 1.0 W/m²K.

As one could expect, the minimum requirements are usually most demanding in the North compared to the South of Europe. What is more interesting is that for the Center of Europe, the requirements set in the ten Central and Eastern European countries which joined the EU in 2004 and 2007 are often more ambitious than in the founding members’ countries. For instance, in Poland, the minimum requirements are set at 1.1 W/m²K compared to 1.3 W/m²K in Germany.

Another fundamental problem highlighted by the Ecofys findings is the absence of updates in the legal requirements. Eight countries have not updated their building codes minimum requirements for at least five years: Czech Republic, France, Finland, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Slovenia and Sweden. In the case of minimum requirements for windows, the absence of updates is expected to be even more important since an update of building code does not necessarily implies an update of the minimum performance requirements of all the building elements. For instance, in England, the minimum requirements for windows remained the same despite the revision of the building code in 2016.

It is interesting to note that two countries have put in place an automated update of their minimum performance requirements for windows to anticipate the increase in the energy performance of windows available on their national market: Poland and Bulgaria. In Bulgaria, the current minimum Uw-value is set at 1.4 W/m²K for windows with PVC frames and shall decrease to 1.1 W/m²K by 2018 and 0.6 W/m²K by 2020. In Poland, the current minimum Uw-value is set at 1.1 W/m²K and shall decrease to 0.9 W/m²K by 2021.

In this section of the paper only extreme cases were used to illustrate the sub-optimal minimum requirements set in Member States and the absence of updates. While extreme cases were used, the same two loopholes that negatively affect the minimum requirements apply to a majority of countries (see table 1).

Scope and implementation of the legal requirements

A third finding of the study is the problem related to the scope and implementation of the legal requirements for windows in national regulations. It is important to note here that the Glass for Europe’s study by Ecofys report (table 1) shows the minimum performance requirements for window replacement in the residential sector when these exist. In practice, their implementation and scope differ due to conditions added in the national regulations, generating de facto loopholes in the regulation. It results that, in those countries, windows not meeting the minimum requirements could be installed under certain conditions.

Glass for Europe’s study by Ecofys shows that in only 11 Member States (out of 28) the minimum requirements for windows apply to single window replacement; i.e. Austria, Cyprus, Denmark, France, Hungary, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Romania, Spain and the UnitedKingdom. It results that the residential market in those countries is limited to windows with a performance equal to the minimum requirements or higher.

For 11 Member States, the Glass for Europe’s study by Ecofys shows that conditions are set for the application of the minimum requirements to window replacement; i.e. Belgium, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Poland and Portugal. In other words, windows for the residential sector with a performance below the minimum requirements could still be installed. These conditions to the application of the minimum requirements are often based on the need for town permit prior to the renovation or minimum area to be renovated. For instance, in Belgium, the minimum performance requirements apply only if a town planning permit is required. Another example is Germany, where the minimum requirements apply only if 10% or more of the building component area is concerned.

It is worth to note here that Finland reported that, despite the conditions allowing windows with a lower level of performance to be installed in the residential sector, almost 100% percent of the renovation market fulfil the minimum requirements as manufacturers do not produce windows below those requirements. No other countries reported the same market trend in the research.

For six Member States out of the 28, the study has not been able to confirm if conditions apply to the minimum requirements for window replacement; i.e. Bulgaria, Latvia, Netherlands, Slovak Republic and Slovenia.

The Glass for Europe’s study by Ecofys highlights that when minimum requirements for windows exist in national regulations they are often conditional. One may reasonably consider that the conditions applying to the minimum requirements limit the push to the market for window replacement.

Conclusion

Minimum performance requirements are in many countries not what drives the market towards energy efficient products, since they often refer to sub-optimal choices and apply under certain conditions. To make minimum performance requirements a driver, the EU legislative framework currently under revision (EPBD) could be improved to be more effective. Glass for Europe’s study by Ecofys tend to demonstrate that although the legislative framework forces Member States to set minimum requirements it fails on two aspects: the lack of guidance on how to best assess the energy performance of windows (i.e. energy balance) and its flexibility which allows Member States not to properly implement it.

In view of the current EU political context, it is unlikely that the EPBD could be strengthen and be made more stringent vis-à-vis Member States in its current revision. Therefore, the work to improve the minimum requirements for windows needs necessarily to be made in countries, with national authorities.

This paper identifies three elements that need to be improved to achieve that objective: Firstly, when outdated, sub-optimal or based on the sole U-value or separated U-value and g-value, minimum requirements should be reviewed and be based on the energy balance approach. Secondly, national legislations could include milestones with automated update/review of the window minimum requirements to anticipate the increase in the energy performance of windows available on their national market. Thirdly, minimum requirements for windows shall apply to new buildings, major renovation down to single window replacement.

1See for instance the International Energy Agency study on “Capturing the Multiple Benefits of Energy Efficiency”

2Preparatory study on window energy label (2015) – preparatory study (Lot32)

3α and β in the Energy balance equation refer to climate data specific to the location of the building; i.e. typical outdoor temperature and solar irradiance across the year

4Preparatory study on window energy label (2015) – preparatory study (Lot32)

References

Buildings Performance Institute Europe (2011) “Europe’s Buildings under the Microscope. A countyby-country review of the energy performance of buildings”.

European Union (2010), “Directive 2010/31/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 May 2010 on the energy performance of buildings”, 2010/31/EU, 19 May.

European Union (2015) “Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee, the Committee of the Regions and the European Investment Bank, A Strategy for a Resilient Energy Union with a Forward-Looking Climate Change Policy”. COM(2015) 80 final, 25 February.

European Commission (2016), “Proposal for a directive of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Directive 2010/31/EU on the energy performance of buildings”, COM(2016)675 final, 30 November.

International Energy Agency (2015), “Capturing the Multiple Benefits of Energy Efficiency”. Glass for Europe study by Ecofys (2017) “Minimum performance requirements for window replacement in the residential sector”.

TNO Built Environment and Geosciences (2011), “Glazing type distribution in the EU building stock”, – February 2011.

Websites

Preparatory study on window energy label (2015) – preparatory study (Lot32)